We’re proud to host this extended piece of writing from RK, who has been supported by OTR. It’s a fascinating exploration of mental health and art, and how creating art can help the healing process. Thank you RK for sending this in and allowing us to host such a thoughtful piece. Please note:

- This piece includes some of the young person’s experiences and opinions at the time of writing, which are subjective

- The young person recognises that the piece is also still a work in progress, and that the piece could possibly benefit from some more direct references to statements, such as which of the links in the appendix these have been drawn from

- The young person believes the piece could benefit from some more examples of stories from people who’ve benefited from using art (and suggests Mind and TheMighty are good websites to find these)

- The piece talks about art, in terms of painting and art works, rather than literature and performance

1 / 6 – Introduction

Personal Motivation

I’ve chosen to focus on the role the arts can play in mental health because I believe that it can be hugely beneficial. With that I’ve tried to make something of a case that would illustrate this as well as reflect some of my personal opinions. The reason I’ll be writing about this is because of mental health issues I have experienced. Being able to express myself, get cropped -and cooped up emotions / thoughts / ideas out, and connect with these inner parts of myself through the arts has supported my mental health, and therefore it’s important and relevant to me.

The March Hare, source: Wikipedia

The arts also help meet challenges in health and social care associated with mental health, loneliness, long-term conditions and aging. I’ll be exploring how art can be a very helpful, if not an essential, part in supporting people’s mental health. I want to present my argument and ideas for other people to consider who might potentially benefit from its support but may need more reassurance and awareness about its value. I have drawn suggesting evidence together from a wide range of areas (such as medical history, art history and present day practices) to present the arguments and evidence of the arts in supporting mental health. I will be drawing on a variety of sources including: evidence based research around art for mental wellbeing; articles on the subject; feedback from individuals’ experience; and artists exploring mental health as part of their arts practice.

Context of Mental Health in the Early 21st Century

The worldwide prevalence of mental illness is common. In the UK, 1 in 4 members of the general population (often even higher amongst minorities and disadvantaged people) annually experience a mental health issue and it affects thousands of people, their friends, families, work colleagues and society. Most people who experience mental health problems can recover fully, or are able to live with and manage them, especially if they get help early on. But even though so many people are affected – in the UK, only as recently as 2010 The Equality Act made it illegal to discriminate directly or indirectly against people with mental health problems; and mental illness is protected as a disability under the disability awareness act – there is still a strong social stigma attached to mental ill health. I think this is very often exacerbated by stereotypes and misrepresentation through distributing outlets of, most often ignorant, intentionally fright-inciting and commercially self-interested mass-media publication traps, that do nothing to educate or non-biasedly expand people’s awareness.

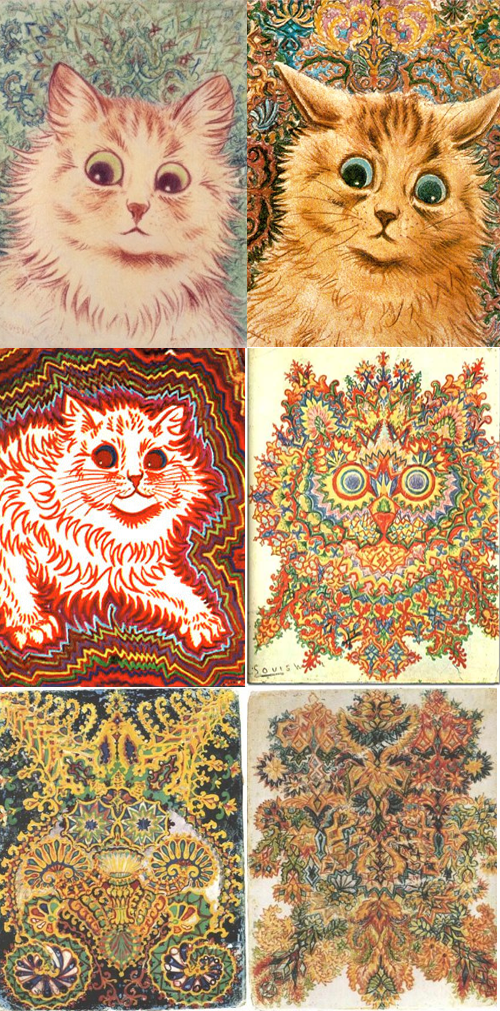

(Potential) progression of Louis Wain’s schizophrenia, expressed in one of his art pictures of a cat, source: Wikipedia

Social Injustice and Mental Health

People with mental health problems can experience discrimination in all aspects of their lives, because there is generally a high number of people in our relatively more local and global societies with stereotyped views about mental illness and how it affects people. In fact mental illness ranks among the most critical health problem in the global burden of disease, and the stigma associated with it is reported to be at the centre of both individual (e.g., low service use, hindered progress towards recovery) and system problems (e.g., inadequate funding of research and treatment infrastructures.) Is education about self-care, mental resilience and mental health lacking in schools and from parents? Are academia, (production-line-like) achievement and technology in many of the capitalistic spheres of the world reinforced by the acts of people in propagandising media and (yet unsubverted) cultish governmental power structures? How obviously aware are people about the lack of support offered, and that these points just mentioned are placed over people’s care and wellbeing?

As a result of this people with mental health problems are amongst the least likely of any group – be it racial, ethnic, sex, age, class, those with a refugee status, with a long-term health condition or physical disability – to:

- Find work

- Be in a steady long-term relationship

- Live in decent housing

- Be socially included in mainstream society

As these are all linked to mental ill health stigma and discrimination they can trap people in a cycle of illness.

Source: Peterson Air Force Base

Governmental Policies and Mental Health

Scientific and governmental elites, as opposed to the little man, can majorly fund to put a Rover on Mars in their intended-to-impose, international and political power games. However, I think these are things that can built 10 years later as well, or just not be built at all. I definitely don’t think it’s a priority at present – there’s no need to further reinforce the dysfunctionality in the world -and power games of our societies’ self-oriented-politicians and elites’ comprised systems. As some people may be aware, we don’t know half as much about what’s in the water of the Earth’s oceans, our own bodies, and more importantly how our brains function – why don’t we look into these matters first before moving on to the next planet or other (trivially) external matters?

Mental illness is stigmatised, potentially over-diagnosed, and often misunderstood. And while many of the former horrid ‘lunatic’ asylums don’t exist in their exact roles and forms anymore, the help that various people are, or potentially could be, getting as they are sent into the community nowadays often doesn’t work and doesn’t provide them with enough support – leaving them perpetuatingly disadvantaged or worse. So what is going to be done to change that over the next few years and further into the future? What are right-wing governments, like the one currently in this country, going to do to change that they’re somehow still not doing enough to support the needs of various people with mental health issues? How can more positive changes be put in place that address these major issues around access to services, social inequality, misappropriation of funds and misrepresentation?

Imbuing Movements for Change

Scientists are still learning new things about where conditions come from, while sufferers try to catch up with the ‘truths’ and figure out how to cope. And while there isn’t enough of this reducing stigma and promoting good mental health and community care yet – as well as these areas very often being underrepresented and misrepresented – there are also organisations working hard to: increase people’s knowledge; awareness; improve people’s attitudes to implement fundamentally paramount changes to these in the current societally operating systems; reduce stigma to promote so much needed mental -and overall wellbeing; and much better enable and empower people’s personal recoveries.

2 / 6 – My Personal Experience with Art

Art has helped me with my mental health in at least the following ways:

- Given voice to certain aspects of my being,

- Contained the emotions from the art and got them ‘out of my system,’

- Helped me to channel a feeling, state and / or mood,

- Created a sense of freedom and security for me,

- Helped me to explore how I feel,

- Has been a creative medium that is a safe and soothing distraction,

- Has been able to help me sit with any feelings and thoughts,

- Helped me notice and acknowledge difficult feelings and / or negative thoughts.

OTR’s ‘Inspiration Works’ creative drop-in studio

Exploring Emotions

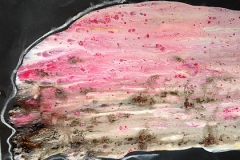

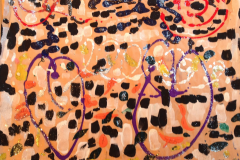

I think if we don’t acknowledge our feelings we can lose ourselves. Using art can be very helpful by allowing me to explore different materials while expressing how I feel. I can make what I want to make and how I want to make it, which includes using shapes, composition, colours, mark making, textures and styles such as abstraction and realism. I can connect things, pull them apart, relocate them, set up a different part or scene to something, expand on something making it larger or smaller, do a different version(s) on something with different parameters. Different materials can have different smells, textures, sounds and weights so working with them can offer sensory support as well. From my experience it can also play a very significant part in helping when I may be going through an existential crisis, enabling me to channel my inner difficult thoughts and feelings, which can help me understand myself and the world around me.

The Process

As everyone is different the process of expressing can be different for everyone, but what I get from doing art is that it can generally make me feel and be more in touch with my emotions. This can be through sitting with them as well as expressing them in various degrees and mindfully working through stages of releasing and processing them more. It can also enable me to feel some other beneficial, eg. more ‘positive’ (ie. that bring me up) types of feelings that can be good for me and help me with my mental wellbeing. It can be feelings that give me a sense of: calm, relaxation, gratitude, surprise, impressed, playful, relief and satisfaction, which I find helpful.

Materials

Different art materials and ways of using them can give me a variety of art experiences and enable me to learn different skills that can help me find other ways to express feelings, thoughts and states of being. Using textures offers a sense of release, colours I often find great to express moods and feelings, whereas clay can help me feel safer (which may be due to its sensory features of smell and touch.) Also, depending on how I feel I’d want to use the clay it can enable me to get big, real and strong emotions – which sometimes have lots of force in them – out, ride them out and process them better (rather than becoming bottled up and ‘stale’), which all culminates into allowing me to be alleviated from them. This, I know, is something that helps me with my mental and physical wellbeing more. As mind, body and spirit are interlinked I feel this is so important in enabling me to deal with these feelings, both in the shorter term as well as in the longer term.

Communication

Art can offer a form of non-verbal communication, which has allowed me to express areas of my being, about my life or myself, which at times may be difficult to talk about or find the words for to express. The arts can help to express the intensity of a feeling in a way that gets it out of my system. This can also be very useful to help process strong emotions such as anger. How I then follow up dealing with these feelings is by eg. just sitting in them; riding them out; shifting my attention by doing something different that helps me to take my mind off of it; talking to someone about them; having a soothing cup of tea; and being around other people who I know it’ll be safe to be around. Talking to supportive people and using creative outlets are generally particularly helpful approaches for me. It’s a good thing too that, naturally, no one can take your emotions away from you, and it’s okay too to still be learning how to manage them. This is why I think expressive therapies such as art therapy can be so useful for people who maybe may find it hard to talk about certain feelings, because they’ve mentally not connected words that much yet to how they feel.

Group Working

Being in a group of other individuals doing art can also come with a positive social aspect, eg. allowing you to engage in games of making joint art pieces, and / or share impressions, experiences and different viewpoints based on each other’s art; as everyone’s naturally (bio-physiologically and psychologically) different, sees things differently and has had different experiences, these are qualities that everyone can often offer each other.

3 / 6 – Mental Health and Art in History

Mental Health and Art in Prehistory

Art for mental health is not new, but has only relatively recently been recognised. Its roots are ancient, universal and identifiable as a language for mental, emotional and spiritual healing. Life is art so people are artists, I think. From what is (thought to be) known, art had generally been practiced globally since at least the “late” Pleistocene Stone Age, 38.000BC by primeval communities, that had dwelled around cavelike shelters and used art for expressing, empathising and to be an aspect of communicating a language. The caves with this art, shielded away from the elements, are examples of ones that’ve maintained this. These prehistoric artists who drew animals on the walls of caves, or who carved fertility figures, old Egyptian painters of protective symbols on mummy cases, old Buddhist and Hindu creators of sand mandalas, old Celtic metalwork inscribers of intricate motifs, old African carvers of ritual masks, old Byzantine painters of sacred icons, old Ethiopian artists who drew on parchment healing scrolls, old Zuni carvers of magic fetishes – all represent historical antecedents of modern art for mental wellbeing.

Prehistoric art in a South American cave, source: Wikipedia

Theories on Mental Health from Early Civilisations

There’d been an exponentially global increase in arts practices – such as sculptural and carved designing, mural painting (frescos), metal work and mosaic, gemmed and glass work – since the “late” Pleistocene Stone Age in various communities and societies (provided these had an agriculture-practicing foundation) as people started being more exposed to art and art experiences. Some of these, such as Ancient Greece (1200BC-600AD), had a few different theories on how they viewed mental ill health and how they thought this could be connected to the arts. In fact, some people in Ancient Greece may’ve been one of the earliest in a historical civilisation to have employed more considerate approaches towards those who were struggling with a mental illness, and this is something that has since played a significant role in our history of medicine. Intermittently throughout periods of their civilisation there had been three basic theories that they used to diagnose psychic phenomena, such as:

- the organic (the attempt to explain diseases of the mind in physical terms);

- the psychological (the attempt to find a psychological explanation for mental disturbances);

- and the sacred approach (ascribed through their religion and can be further divided into the animistic, mythological and demonological models.)

Speculative depiction of Plato from Raphael’s School of Athens, source: Wikipedia

Some of the earliest, well-known, Ancient Greek philosophers, who we have remainders of – Thales of Miletus, Anaximander and Pythagoras (all 500s BC) – had strongly influenced their cultures, as well as the wider world, from their ideas on the organic and physiological aspects in treating mental illness. They show that physiological and holistic therapies have been a thing for almost forever, so (as our largely-Ancient-Greece-derived society) why aren’t these things that we have thought about more?

Ancient Greek Theories on Mental Illness as Physiological vs. Sacred

The physician Hippocrates (400s BC) (considered the father of Western medicine), as well other individuals from physiological schools of teaching, thought of various mental conditions, eg. schizophrenia and epilepsy, as “sacred diseases” that were physiological syndromes by nature. Some of these progressive Ancient Greek people – who had many investigative, concerned and enlightened traits – tended to have a natural and humane approach to mental illness by closely associating it with physical sickness. They stressed the importance of understanding the patient’s health, independence of mind, and the need for harmony between the individual, and the social and natural environment to underline a philosophy of care, holistic model and component of “A healthy mind in a healthy body.” In the same period philosophers Socrates and his student Plato (also 400s BC) and their schools of teaching opposed the ideas of the physiological and thought more of the superstitions of Ancient Greek religion – the whims of the gods, who were a touchy lot and quick to take offense – as a fallback explanation. Their overriding concepts on ‘madness’ stated that there were four types of ‘divine madness,’ each ascribed by a different god.

Mental Health in Ancient Greek Tales

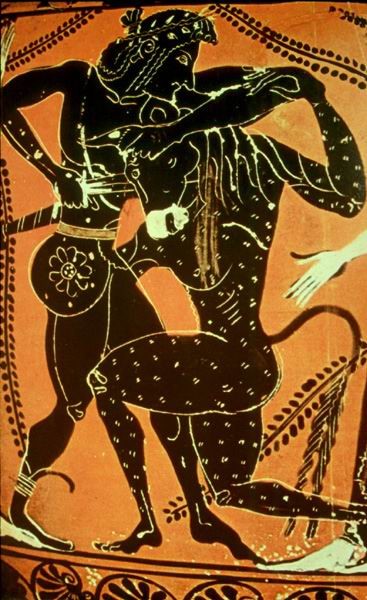

There are a fairly large number of remaining Ancient Greek myths and tragedies that (could be speculated about) reflect a large spectrum of various states of mental health. This can eg. be seen in the writing about their characters’ expressions, actions, or various states bestowed on characters through some of the mythological god’s supernatural abilities. And while various artists in some of the following eras have tried to depict images based on these tales merged with their own interpretations, I haven’t necessarily been able to tell whether this art had been used to express thoughts and feelings that related to mental states of the artists. As far as archaeological evidence suggests to us, there was very little art that had consciously been used by people from this historical period to help express different states of mental health. But with there being so many paintings of different types of Ancient Greek heroes, I wonder which of these could bear visual similarities to our modern ideas of one’s inner hero of self-care, and resilience, in the face of mental distress? Are there also depictions like these that are based on people who support others?

Speculative depiction based n the Ancient Greek tale of Theseus and the Minotaur, source: Wikipedia

Other examples: Colour and Geometry

Some other examples of how art had been used in different cultures as a tool for treating mental health are in colour and geometry. Found to have somewhat been used for spiritual and therapeutic purposes in two nearby lying areas of Ancient Greece and Ancient Egypt, it was noticed that living beings appeared to be vitalised by the bright reds, oranges and yellows of daylight – and calmed and rejuvenated by the blues, indigos and violets of the night. N.b. the influence of this didn’t spread much into the cultures of Dark Ages Europe – which were socially plagued by many religious power structures, austere doctrines and persistent inequality of social class – until a slight blooming hope of change had started the 15th century Renaissance. Further east, in areas in Asia, some people thought that repeating geometrical patterns (sometimes with colour) had some visual and spiritual impact on the viewer. Diagrams like these (sometimes called ‘mandalas’) have symbolically continued to be used for a long time by some Asian religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism. However, ascribing symbolic and sacred meanings to certain geometrical shapes was something that had been used across the board in the global history of a lot of religiously constructed designs, notably in larger religions.

Geometrically patterned image from a contemporary adult colouring book, source: Pixabay

Art in Global Medical History pre-1900s

In medical history, art for wellbeing hadn’t been recognised and didn’t start to be used more frequently until the 20th century. Before that there had only be a small number of (supposedly) psychiatric institutions since the Dark Ages. London’s Bedlam is a good example of this. In Western European asylumic systems from the late 1700s onwards, the sporadic usage of arts for patients patronisingly used to be called ‘moral treatment,’ and had been derived off the back of then-contemporary philosophical ideas. However significantly progressive figures in the 1800s strongly opposed the coercive and barbaric treatments of previous times and brought about important and influential views. They also introduced various types of arts activities in psychiatric institutions and strived for those to become more commonplace, bearing similarity to today’s secular and holistic views. Some examples of people like these were: William Browne, William Battie, William Tuke, Vincenzo Chiarugi, Benjamin Rush, Dorothea Dix and John Conolly.

Art in Global Medical History post-1900s

While there’d been a growing body of clinical work (derived from inhumane, neuroscientific and surgical pioneering work) in the mid-1800s, and followed on continued neuro-analytical and psychological work by figures such as Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud, it had been clear for a very long time that these medical methods and interventions – despite, that I believe, were being favoured by aristocratic elites to further, unethically, impose them onto patients for power – were inadequate and inappropriate and not providing enough holistic treatment needed for patients’ healing and recovery. This continued until the first part of the 1900s until there were two figures, Adrian Hill and Edward Adamson who were much more receptive to the needs of patients to verbalise and express themselves. They argued in favour of art for healing and tried to pick the creative approaches from previous centuries up again, as well as better integrate them into a holistic treatment. This was a much bigger success and saw major mental health improvement in those few who experienced it, in contrast to clinically conventional, obsolete and cruel lab-rat style methods run by bodies of elite psychiatrists. In fact they used damaging types of chemicals – such as chlorpromazine – and chairs – such with ECT (electroconvulsive therapy, formerly known as electroshock therapy) – which they barbarically and neglectfully imposed their patients to – which I think were even madder than the mental illnesses that patients experienced themselves. All in all these invasive and forceful methods showed that the medical elites at the time essentially still had no idea what they were doing. Cognitive therapy was further founded in the 1960s by psychiatrist Aaron Beck. As touched on in the introduction, since many of the ‘lunatic’ asylums – that failed to address mental health issues effectively and ethically – have closed, the often resultant insufficient levels of concentrated community care continue to pose various major issues such as deprivation and life-threatening conditions to those suffering from mental ill health in our societies.

Science on Art, Mental Health and the Historically Evolved Human Brain

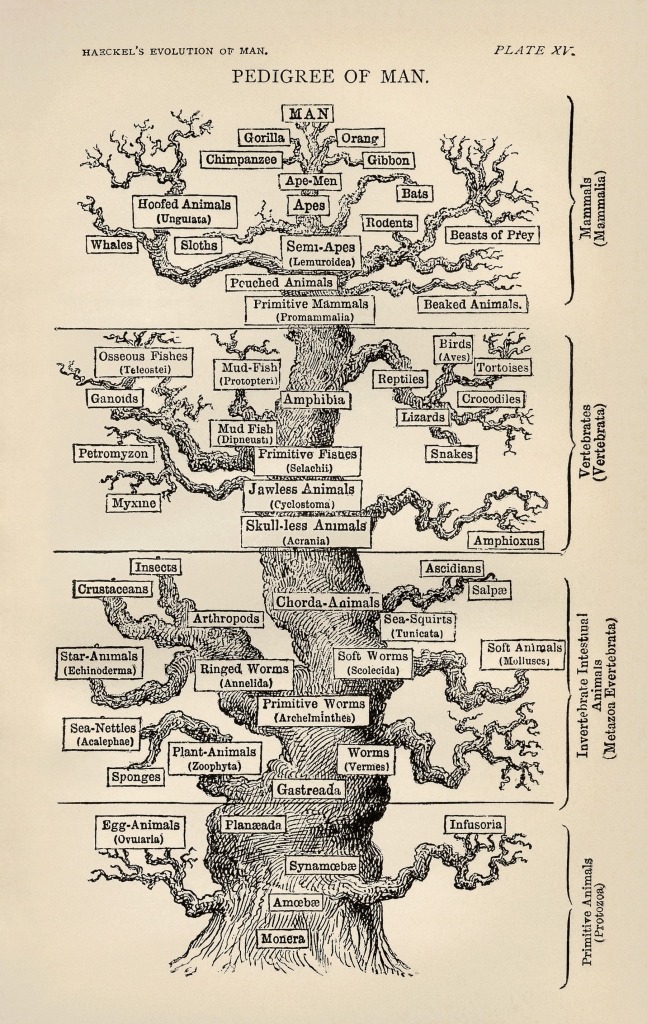

The science on human brains gives evidence to suggest that which has been described by many people who’ve used art and found it beneficial, which is that the make-up of our brains has been bio-engineered in such a way that its basic functioning mechanisms benefit from the usage of expressive art. Researchers of anthropology, psychology and art have also looked at which areas of the brain are activated when people participate in or view art, and why this is important to group dynamics that are linked to the development of our creativity and social action. One aspect that underlies this is how cognitive development in the human species has progressed, which C. Darwin in his Theory Of Evolution had observed involved: natural ornamentation, external courtship displays as a means to attract potential mates, and other shamanistic activities such as group activities, chanting and vocal iterations involving ritualistic and communal dances. Another aspect is that ‘processes’ like these involve social behaviour that stems from evolutionary animal rituals in pre-mammals (that lived pre-300 million years ago), who used ritualistic behaviour to signal social functionalities, facilitate interactions between the species and contribute to cooperative group dynamics. These activities of imitation through iterations are functional and systemic of group communication, as they coordinate goal driven activity and foster formations of important parts of the brain, including primeval, social, emotional and memory brain functions. In primates it had been observed that communal chimpanzee alpha-male rituals demonstrate shamanistic practices, which involve emotional vocalisations, drumming, and upright charges meant to provide community integration. This behaviour imbued a protectiveness of the group and culmination towards emotional release by all. When observed in humans day to day we might call this holistic and / or creative, and this can parallel how art can be used to express the states of our mental health, both as individuals and / or in our communities. This can pose another question: why and how is it that that we – in our shared evolution on this planet and its given conditions – have been designed like that?

Depiction of Ernst Haeckel’s evolutionary pedigree of man, source: Wikipedia

4 / 6 – Supportive Evidence for Mental Health and the Benefits of Art

I have drawn much of my evidence from the following three articles. Some include quotes from mental health experts, some art experts, some both of these and some quotes from people don’t fall into either of these two categories.

A – The Big Anxiety Festival, The Guardian, 2017

From having read about this festival it looks like it’s quite a large arts and mental health festival with various installations. The work that’s on display seems to offer some good conversation starters, eg. how the arts can cross over into the health sector. One of the highlights seems to be the importance of people telling their story, both in expressing through the arts as well as through an outlet such as a festival. The festival has a large community interest, seeks to make people more aware that everyone has a mental health and bring people together on a primordial level, to recognise and suggest a good rapport between them.

Quotes from Prof Jill Bennett who’d conceived the festival, stated that: “There’s a lot of evidence that art has a lot of impact when it comes to mental health. It’s not just a diversion – there is evidence that it impacts on mood and wellbeing,”

“Mental health is the one area of health where there are no cures. Some things work a little bit, but not completely. But maybe the arts can be part of the mix. There are very few areas of medicine where you could say that. But we haven’t really systematically explored the effects of arts on mental health.”

“What art does is to provide the rich forms of engagement and thoughtful communication.”

B – With Art in Mind exhibition, Design Curial, 2017

From having read about this exhibition it looks like it’s done a great job in exhibiting a wide range of mental health influenced art work by relatively well known artists and bring these to the awareness of a wider audience.

Megan Ruddlesden, Events & Community Fundraising Manager at the Mental Health Foundation said: “The arts are an incredibly powerful way to talk about mental health – to share experiences, tell stories, reduce stigma, and change minds.”

“We’re so excited about the Mental Health Show art exhibition with Zebra One Gallery, which will further highlight the invaluable link between mental health and art.”

C – Contribution arts can make to health and wellbeing, The Guardian, 2017

From having read this article it looks the author has drawn their views from credible sources and research, and present both the viewpoints from arts and mental health professionals and a client’s viewpoints.

Quotes:

Gavin Clayton, executive director of Arts and Minds: “The arts are important for wellbeing because beauty has a role in our lives. If we don’t listen to that, or pay attention, then that can cause problems.”

Lord Howarth of Newport, co-chair of the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on arts, health and wellbeing: “The time has come to recognise the powerful contribution the arts can make to our health and wellbeing.”

Phil George, Wales Arts council chair: “It helps people to relate to their own experience in a new way. I’m convinced from the evidence that investment in the arts for health would pay off. It would be beneficial, not just in terms of wellbeing, but in terms of the pressures and costs that mental illness puts on the system.

Karen Allen, an art for wellbeing user: “…if you’re feeling depressed, the simple act of being in a room with other people – where you’ve got the space and time to just be yourself – really helps to improve your mood. There’s such a feeling of camaraderie and friendship. The art is almost a happy bonus to that connection. While you’re mindfully doing the art, it frees up your personality that had maybe been buried. It takes you away from whatever is bothering you, just for a couple of hours.”

https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2017/oct/11/contribution-arts-make-health-wellbeing

My Views on the Evidence from These 3 Articles

I agree with everything these people have said. Depending on how you’re feeling and what state you’re in there can be benefits to both a group and individual art making setting. I’m glad to have found examples of input like these from other people, backing how art can and has helped others with their mental health, as I benefit from the experiences. This shows that art on prescription, as an alternative to medication, is effective to be used more when people experience mental health issues, as it’s evidence based. The supportive benefits that art can offer someone’s mental health are more commonly understood, and often a general notion, for larger national, and international, bodies of counsellors, therapists (such as expressive therapists and psychotherapists) and spiritual healers.

5 / 6 – How Other Artists Have Used Subjects of Mental Health in Their Art Practices

Apart from the previously mentioned people who’ve made art that has been drawn their experiences with their mental health, I‘ve researched a number of other artists, who visually address and / or explore their mental health in the mediums of their arts practices. The ones I’ve included are most likely only a snippet that scratches on the people who, in some way, have used art to express the experience with their mental health, however who I think they can give a real temporal overview of how artists had used this and the potential that they saw in expressing various states of their mental health through art. Some of these people are internationally renowned, and some are local to me in Bristol.

From looking at the work of international and local artists it was clear to me what the value of art was to their mental health. Which I thought was especially the case for some of the artists at the time when mental health was not necessarily a concept people knew a lot about or had been made aware of. So, although some of them did not consciously use art to express their mental health we can speculate and make educated guesses now about where we can see this in their work (and in relation to what has been left to us about their lives.) And I think it’s likely that for many years artists had used art for mental health without being aware that that was what they were doing. Some of the artists that I’ve included in the “previous” section may not have used art to express the state of their own health but rather visually commented from an outsider’s point of view – as opposed to art which had been made from a personal point of mental health experience – on the situations and events that involved the suffering of others in their time with mental ill health.

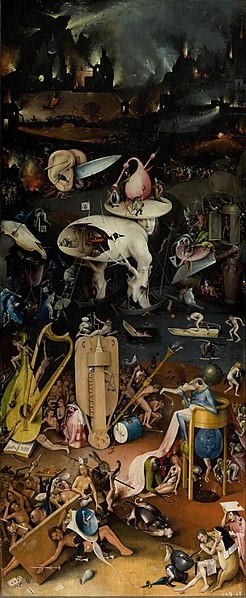

Hell, from The Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymus Bosch, source: Wikipedia

Though not a hard-and-fast rule, some thematic aids that I’ve used and looked for to help me identify whether an art work might be coming from an artist’s experience with their mental ill health I think can be found in the features and expressive finesse of the: psychedelic, surrealistic, spooky, satirical, terror and / or dread, as well as other feelings-related pieces and any other art based on how people at different times might’ve viewed mental ill health (eg. through religious exorcising / ‘devils’ / ‘monsters’/ ‘madness’ / ‘insanity,’ as they called it.)

Previous:

Apart from possibly some of the Classical Art as an early reference point in the history of global art, it seems to be more difficult to find Medieval artwork dealing with the subject of mental health. This is possibly both due to the highly religious and traditional cultures then and very specific outlines that producing artists were ordered to follow through aristocratic power structures – which made it harder to create work that was centred around the states of people’s being, authenticity and the ability to express.

- Master of the Saint Bartholomew Altarpiece (artists’ pseudonym) – St Bartholomew Exorcising (mid 1400). In medieval times strongly upheld Christian doctrines had raised convictions of ‘evil spirits’ which were used as a fallback explanation for many things.

- Hieronymus Bosch –The Garden of Earthly Delights (1500) – a large triptych, consisting of three paintings that depict: a natural and somewhat peaceful world; a fantastical, surreal and frenzied natural world; and a hellish world, that surrealistically depictions major world – especially human inflicted – terrors. – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_paintings_by_Hieronymus_Bosch

- Albrecht Durer – Melancholia (early 1500). To this genius, forward-looking Renaissance artist, Melancholy – at the time observed and described as “a darkness of the mind resulting from an imbalance of the humours (ie. blood, black bile, yellow bile, phlegm)” – was the badge of genius, and as he stated: “to aspire, to know and create is to slump into despair. Unhappiness is noble.” – https://www.albrecht-durer.org/

Melancholia, Albrecht Dürer, source: Wikipedia

- William Hogarth – A Rake’s Progress (8 paintings and their engraved copies) (early 1700) (this work focuses on showing (in an almost ‘storyboard’ series style) the decline and fall of a spendthrift aristocrat in London, who spends all his money on things hedonistic (extravagant luxury, promiscuity, and gambling etc.), as present at the time in early 1700s London, as his mental health – which is implied from the states the person had been described to be in – and wellbeing deteriorate. Then through a series of events he ends up in the debtor’s prison and is later permanently admitted into a ‘psychiatric institution,’ London’s notorious Bedlam at the time. – https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/search/actor:hogarth-william-16971764/page/2

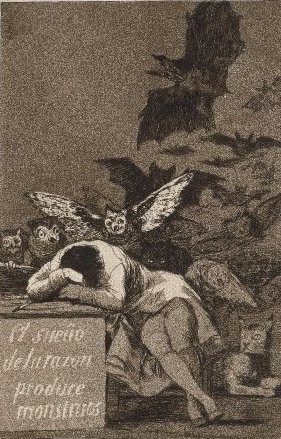

- Francisco Goya – The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (one of an extraordinary set of 80 etchings in which the artist had focused on the universal follies and foolishness of the society he lived in) (1800). This work – at the time of the great 18th century movement that sought to change the world with encyclopaedias, scientific demonstrations and the first factories – shows a ‘scientist’ or other rational thinker and the idea that there are those who once they don’t give in to their compulsions in the sciences are being tormented by dark thoughts -and disturbed mental health. This suggests that they could be creating self-fulfilling prophecy cycle that keeps, hard-line, driving the sciences and deterioratingly neglecting their own and others’ needs. I think this is still even pretty relevant and similar to how various aspects of societies nowadays take place. – https://www.franciscodegoya.net/

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Francisco Goya, source: Wikipedia

- Jean-Louis Gericault – Portraits of the ‘Insane’ (one of 10 paintings) (early 1800). In this painting, with an introspective mood, he expresses deep respect and human sympathy for a woman whose illness would seem mostly visible as deep unhappiness. The majority of this artist’s work dwells on death and violence and in this painting he tries to evade stereotypes and prejudice by showing another side to mental ill health, and visibly portrays mental illness as a human condition that he feels close to himself. – https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/romanticism/romanticism-in-france/a/gricault-portraits-of-the-insane

- Gustave Courbet – Self-Portrait (The Desperate Man) (mid 1800) (after Albrecht Durer’s The Desperate Man in early 1500) Image of a facial look possibly expressing feeling ecstatic and terrified. He thought as equating madness and genius. An artist who went on to initiate a style of painting from the 1850s that became known as a realism style of imagery painting. (Interesting fact about this artist that) on the basis of the destructive effects that nationalism has this artist had written to the Government of National Defence stating: “In as much as the Vendome Column is a monument devoid of all artistic value, tending to perpetuate by its expression the ideas of war and conquest of the past imperial dynasty which are reproved by a nation’s sentiment, citizen Courbet expresses the wish that the National Defence government will authorize him to disassemble this column” and moved to a more appropriate place such as a military hospital. – http://www.gustave-courbet.com/

- Vincent van Gogh (late 1800s) Starry Night – the swirly, heightened sense feel of the painting could reflect a state of anxiety or hallucinations – https://www.vincent-van-gogh-gallery.org/

Starry Night, Vincent van Gogh, source: Wikipedia

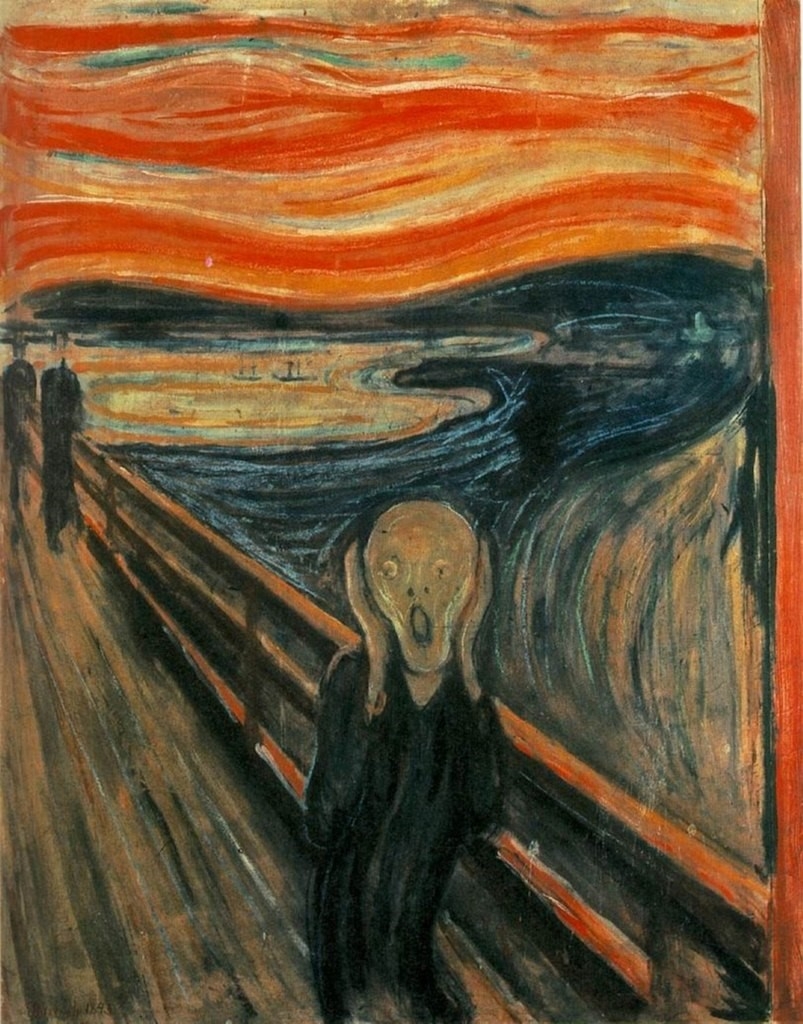

- Edvard Munch – The Scream (late 1800) – the swirly, slightly psychedelic and fairly dark colours in this painting, as well as the bleak, nondescript figure and somewhat despairing facial expression, could suggest a kind of aroused and fearful state related to their experience of a mental health. – https://www.edvardmunch.org/edvard-munch-paintings.jsp#prettyPhoto

The Scream, Edvard Munch, source: Wikipedia

Some other previous artists include:

- Georgiana Houghton (mid 1800s), artist and spiritually inclined person who’s made abstract psychedelic watercolour art – https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/132645151504631872/

- Salvador Dali (early-mid 1900s) – often made surrealistic work that is rife with imagery rendered from his dreams and hallucinations, as well as ready-interpreted symbolism – https://www.salvador-dali.org/en/artwork/the-collection/

- Frida Kahlo (early-mid 1900s) – had made work on some stages of her life and around her identity – https://www.frida-kahlo-foundation.org/

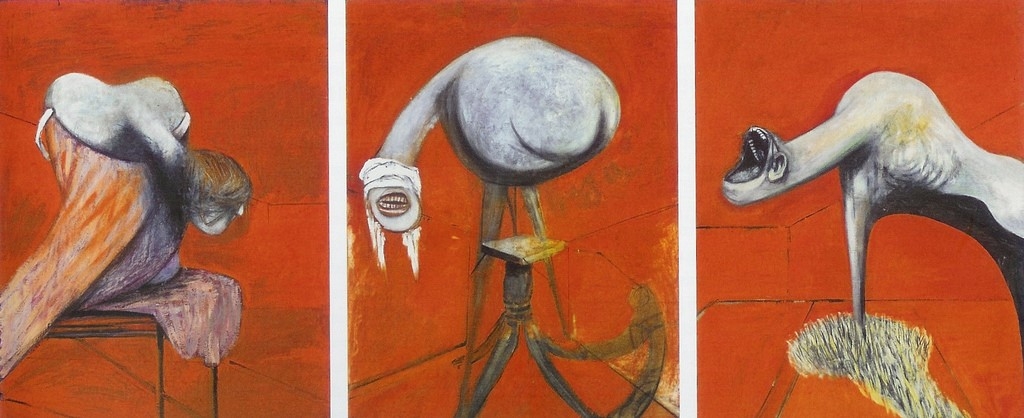

- Francis Bacon (early-mid 1900s) – often made portraits with distorted figurations –http://www.francis-bacon.com/paintings

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, Francis Bacon, source: Flickr

- Louise Bourgeois (early-mid 1900s) – whose works shows abstract, figurative, sometimes feministic ideas – “Art is a guarantee of sanity” is one of the things she’s said –http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/louise-bourgeois-2351

- Mark Rothko (early-mid 1900s) – made some pieces with somewhat abstract and / or gloomy themes – http://www.all-art.org/art_20th_century/rothko1.html

- Andy Warhol (mid 1900s) – made drawings which were often comic, decorative and whimsical as well as pop art which turned to themes of public life and mass society – https://www.gallery.ca/collection/search-the-collection?f%5B0%5D=field_reference_artist%253Atitle%3AAndy%20Warhol

- Jean-Michel Basquiat (mid-late 1900s) – made Punk and counter-culture types of work that brought together styles from different geographical cultures that resulted in a kind of visual collage style – http://www.artnet.com/artists/jean-michel-basquiat/

A number of artists like these can also be found through the “Outsider Art” movement that is often to do with artists’ work that covers subjects of mental health and art https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outsider_art

Contemporary:

A number of contemporary artists include:

- Yayoi Kusma – often pointillist, abstract art and repetition of patterns – http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/yayoi-kusama

- Grayson Perry – often uses ‘unconventional’ materials and themes such as the autobiographical and ones that question contemporary culture, social injustice and class inequality, people’s habits, public life and mass society – http://www.artnet.com/artists/grayson-perry/

- Kim Noble – who’s made both portrait and abstract art http://www.kimnoble.com/virtual_galleries.htm

- Tracey Emin – makes conceptual and figurative art –http://www.traceyeminstudio.com/type/artworks/sculpture-and-installation/

- Gerry Laffy – uses a range of mixed media art http://www.gerrylaffyart.com/

- Lee Du Ploy – creates portraiture art around psychology and the human mind https://www.myartzpace.com/

- Darren MacPherson – makes abstract figurative art –https://www.artgallery.co.uk/artist/darren_macpherson

- Brothers Charlie and Eddie Proudfoot – have been using art as a way of communicating and from a personal place – http://www.huckmagazine.com/art-and-culture/art-2/secretive-siblings-creating-beautiful-defaced-artwork/

- Stifado Dante – has made abstract figurative art – http://www.eddielock.co.uk/artists/stiffado-dante

- Nigel Stefani – makes portraiture art and draws people’s characters – http://www.nigelstefani.com/

- Mason Storm – has made provocative and abstract art – https://www.reloadgallery.com/collections/mason-storm

A local exhibition that has shown art work by young people revolving around mental health is ‘All in the Mind’ – http://rising.org.uk/aitm-collection/ and includes people such as:

- Ailsa Fineron – who’s made abstract and mood based work – http://www.ailsafineron.com/high-whilst-sober/

- Keely Hohmann – who’s made conceptual, conversationally charged work – https://keelyhohmann.wixsite.com/artportfolio

6 / 6 – Conclusion

Despite a long history of art and its benefits to mental wellbeing, support for this still remains pretty low, as well as the awareness about it in some people’s obsoletely retained and tactless mental backwaters. At least in some communities in this part of the world evaluations and statistics have shown – for example through a leading mental health campaigning body called ‘Time to Change’ – that between 2011 and 2015 there’d nationally been a 6% improvement in attitudes towards people with mental health problems. This can indicate that society could slowly be changing and supporting people’s mental health more. However, what present political power structures, cultures’ beliefs and other factors could still be hindering this change?

From what has been outlined in my piece of writing, there is strong evidence to suggest that art can help with mental wellbeing. Scientifically it’s been proven now that with the bio-engineered make-up of our brains – derived from our pre-mammalian, primeval and evolutional days of navigating the various conditions of this world (that got us here today, and as we continue to do) – art has a positive effect on our mental wellbeing.

When it comes to serious forms of mental illness, scientists are still searching for effective answers to understand and better support sufferers – in fact, very much in a similar way as some of our ancestors were – puzzled, frightened and unable to come to terms with what are deeply upsetting and disturbing aspects of our, nonetheless, innate humanity. Historically, there may not always have been obvious evidence to suggest art had specifically been practiced to support people’s mental health, however are the two inseparable?

Both others and myself who’ve used art for their mental health have reviewed the mental, emotional (and spiritual) benefits that this can have for them. A long tradition of artists has seen the significance and experienced the benefits that using art to express themselves – including states of their mental health – have had for them. Researchers and other art and mental health professionals have seen the same positive effects in their subjects, clients or others who have used the arts and creative mediums to help express their mental health. After all isn’t art fundamentally an instinctual need to communicate? Therefore, I believe that mental health and art are indeed inseparable.

Appendix

References

Below are some references that I’ve used and which can be useful resources to find more examples of projects and information about how the arts can help mental health, as well as research about this (including information, statements and further validating experiential evidence.)

Research:

- http://artsandminds.org.uk/research-and-evidence/

- https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/blog/visual-arts-mental-health-and-wellbeing-evidence-review/

- https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Be_Creative_Be_Well.pdf

- https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/projects-programmes-and-initiatives/arts-and-mental-health-creative-collisions-and-critical-conversations/

- http://www.start2.co.uk/files/downloads/Start_MC_downloads/Reports_on_Starts_work/Start_evidence_base_March_2015.pdf

- https://www.instituteforcreativehealth.org.au/sites/default/files/evidenceguidefinal.pdf

- https://www.evidence.nhs.uk/Search?q=art+mental+health

- http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/resources/research

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mZA0V4aLOIM

- https://www.artistsunionengland.org.uk/mental-health-and-wellbeing-resources/

- http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/33373/

- http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/Publications/Creative_Health_Inquiry_Report_2017.pdf

Articles:

- https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2017/jul/19/arts-can-help-recovery-from-illness-and-keep-people-well-report-says

- https://www.psychology.org.au/inpsych/2015/june/gray/

- http://www.baat.org/About-Art-Therapy

- https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news

- https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/your-stories/a-journey-to-recovery-through-art/#.WpPPDRO0NGM

- https://themighty.com/2017/08/putting-anxiety-into-art/

- http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/case-studies/happiness-project

- http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/what-is-arts-in-health/national-alliance-arts-health-and-wellbeing

- https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/blog/community/art-shed-museums-medicine/

- http://www.arttherapyblog.com/mental-health/art-therapy-helps-high-school-students-express/#.WMgjzhicZ7M

- http://www.breathemagazine.co.uk/breathe-magazine-issues/

- https://thebristolcable.org/2017/05/art-to-tackle-the-teenage-mental-health-taboo/

- https://graffitikings.co.uk/mental-illness-street-art/

- http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/

- http://www.artsforhealth.org/news/Arts-Contribution-to-Education-Health-and-Emotional-Well-being.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/gallery/2018/jan/17/eight-artworks-inspired-mental-health-problems-pictures

- http://www.alldaybreakfast.info/unlocked/category/research/touched/

- https://www.bap.org.uk/articles/mental-health-stigma/

- http://www.indiana.edu/~sgcmhs/

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/sep/19/taking-over-the-asylum-art-made-at-bedlam-and-beyond-in-pictures

- https://wellcomecollection.org/exhibitions/bobby-bakers-diary-drawings

- https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/legal-rights/disability-discrimination/disability/#.WvshuC-ZMUR

Projects: